There is an old adage that thou shalt not drink water from a stagnant body. It is ironical that the stability which helps a water body transform itself into an ecosystem, when sustained over a long period, itself leads to the putrid decay of the water body. This has been the case with three institutions in India: Caste, Congress and Civil Services (as listed in decreasing order of decay). These three institutions have played their part in providing remarkable stability to India at different times in history. But, today these institutions confront new ideas and challenges. All three require transformation or else the first may lead to civil conflict, the second will pave the way forward to the decline of our democracy, and the third will hamper India’s ambitions in the 21st century.

There is no doubt that the Caste System provided remarkable stability to the Indian society through centuries of upheavals. There is also no doubt that this institution was an epitome of dualism and oppression. After independence, the political and social ideas unleashed by the Enlightenment were embodied in the Indian constitution. Thus, with a sudden collision, started the duel between the regressive caste values and western liberalism. The caste system has broken down at various joints — more progress has been made in the past seventy years than the preceding seven hundred. Yet, caste-based discrimination and oppression remain a fact in Indian life. Reservations for scheduled castes and tribes instituted by our nation’s founders were not so much opposed until the late 1980s when it became a tool for sectional interests. Deep-rooted animosity between various caste groups has been fuelled after the introduction of reservations for the so-called Other Backward Castes (OBCs). It is ludicrous that almost half of the seats in various government institutions are reserved. It is further inconceivable that the advantage of reservation is not restricted to a single generation but is propagated further. In my view, there is no doubt that any sort of reservation (based on caste, income, geographical location etc. alone or a combination of these) should not go beyond 33% of the total vacancies and must not be availed by a person if either parent has already benefitted from the same. Every single time a new law or parliamentary bill which has anything to do with caste comes before the government or the judiciary, we see violent mass protests — bordering on anarchy — by various caste groups. On the other hand, many caste-based coteries have been established dealing with everything from forming marriage alliances to living in a secluded community. The history of independent India tells us that Ambedkar has proved to be right over Gandhi in advocating that “the real method of breaking up the Caste System [is] to destroy the religious notions upon which caste is founded.”

Under his prime ministership, Jawaharlal Nehru never allowed his daughter Indira Gandhi to become a member of parliament from the Rajya Sabha or contest in an election. Contrast this with Indira Gandhi’s three acts (read sins). First, she broke the grand old Congress party into two to achieve her own rise to power, an unthinkable scenario even for radicals like Tilak and Bose. Second, she and her younger son ran a duumvirate of oppression while fashioning the Congress party and the Government of India to their personal fiefdom. Third, after the death of her younger son, she started honing her politically apathetic elder son and got him elected to the Lok Sabha. This triple breakdown of the Congress’ values provided stability to the party after the death of Mrs. Gandhi when her elder son Rajiv Gandhi was appointed as the prime minister. But, this stability was based on the loyalty to the ruling family rather than to the party’s values. With some setbacks to the ruling family after the death of Rajiv Gandhi, the party again opted for stability rather than transformation. Fast forward two decades and here we are with a fifth-generation Congress president. Surely, it is the only example of its kind in any democratic country that a fifth-generation dynast heads one of the two main political parties. Again, as Ambedkar said, “Bhakti in religion may be a road to the salvation of the soul. But in politics, Bhakti or hero-worship is a sure road to degradation and to eventual dictatorship.”

The institution of civil services provided India a steel-frame during the crucial years after Independence. It has contributed in a multitude of ways in keeping India administratively united and diplomatically agile. But, as India aims to become a world leader in the coming decades, this institution does not find itself ready for the task. The strength of India’s diplomatic corps is one-eighth that of the United States and less than half of Japan! China sends an order of magnitude larger delegations to various international engagements than India. Domestically, civil servants find themselves as being administrative experts but lacking in specialized domain knowledge to understand intricacies of a fast-moving world. Ironically, the civil servants have themselves too bore the brunt of the leviathan bureaucratic state that has been created by their support — a senior official in the Ministry of Finance recently disclosed in an interview that he has to obtain twenty-five signatures before he can leave the country to attend an official event! Currently, it is excruciatingly hard for domain experts from academia or industry to join the public administration at various levels and utilize their skills towards nation-building. At the provincial level, the institution has been subverted by vile lawmakers for their own interests by the use of “transfers threats.” Most of the officers in the system are tremendously competent and are highly admired by the general populace. But, the steel-framed structure is shackling India in chains while crumbling down itself. Invoking Ambedkar a third time: “No man can be grateful at the cost of his honor, no woman can be grateful at the cost of her chastity and no nation can be grateful at the cost of its liberty.”

All the three institutions mentioned above outperformed themselves at different times in history but are not outdated. The tragedy is that the first necessitates extinction but is the hardest to rectify, the second needs overhauling on the inside but the periphery of the institution is content with its present state, while the third only requires structural changes but is not a priority for any government.

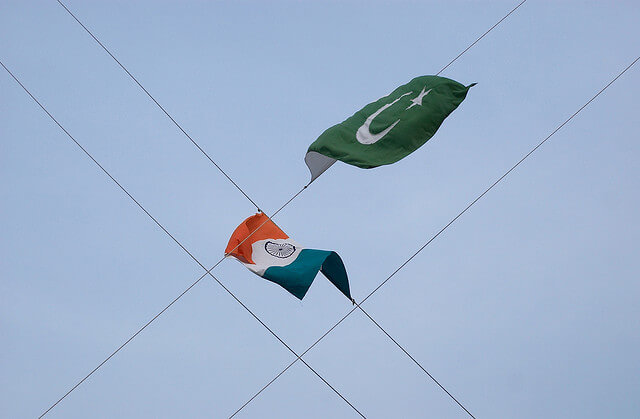

Some Observations on the Recent India-Pak Confrontation

Some Observations on the Recent India-Pak Confrontation