Undoubtedly, the greatest Indian of the 20th century (some may say since Buddha, to which I agree) was Mahatma Gandhi. This apostle of non-violence is still revered across the nation. Gandhi did not believe in justifying the means to achieve the ends if the means composed of violence. In this, the antitheses of Gandhi was Subhas Bose. Just like Gandhi’s teachings, the legend of Bose does not die. Even after conclusive proof of his death in 1945, legends circulated for decades about his escape and eventual comeback to lead the nation. Subhas believed in achieving the aims irrespective of the methods. Indians have always found it perfectly acceptable to revere both Subhas and Gandhi, and therein lies the first dichotomy of the Indian civilization. This dichotomy dictates that violence, as well as non-violence, are equally justified if the cause is sincere. It forced even Gandhi himself to admire Subhas while respectfully dissenting with Subhas’s methods.

India has been the land of Buddha and Mahavira. Both of them significantly influenced Hinduism and Indian civilization. Their teachings are still visible underneath the many layers of the palimpsest that is India’s culture. They preached non-violence and are respected by Indians of all faiths. Jain monks took non-violence to the extreme by following many practices to prevent even mistakenly killing parasites and microorganisms (it is interesting to note that they hypothesized the existence of microorganisms before the invention of the microscope). To suit the prevalent narrative in the Indian culture, even the stay of the Prophet Muhammad in Medina for a few years before he embarked on the conquest of Mecca has been depicted by some Indian Islamic scholars as an example of following non-violence. On the other hand, the most impactful and popular stories across India are the Hindu epics: Ramayana and Mahabharata. Both of them are wonderful tales of love, passion, loyalty, valor, jealousy, remorse, sorrow, etc. In fact, it is said that no human story and no human emotion can be conceived which is not present in these epics. Yet, at the foundational level, each of these tales revolves around war. Both justify the use of violence in certain circumstances. It is striking to think that Rama and Krishna – the greatest warriors – are the greatest teachers along with Buddha and Mahavira – the greatest renunciates – in the Indian pantheon.

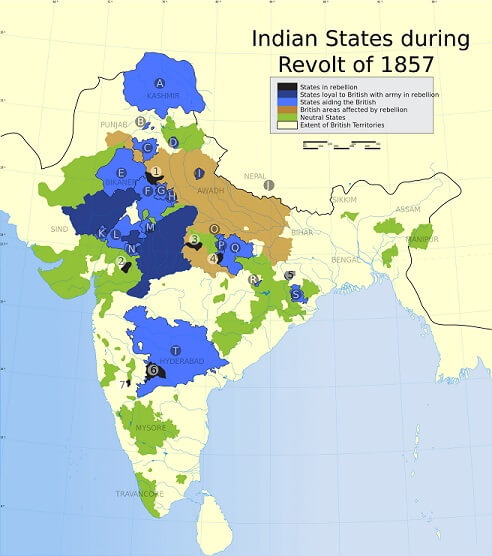

The grandest structure that has been unearthed (literally) at Mohenjo-daro was used not as an armory or as an amphitheater (like the Roman Colosseum to display violent gladiatorial tournaments) but as a public bath. This shows how much those ancient Indians loved to celebrate life. But, make no mistake by only looking at one side of the picture. This is the same India which saw the Aryan conquest and series of invasions following it. Even the tales in the Puranas which are our source about many of these invasions talk repeatedly of wars between gods and demons. Again, in India, it is normal to name one planet as Mangal (relating to peace and bliss), another as Shukra (related to the name of the demons’ teacher Shukracharya), and a third as Brispathi (the name of the gods’ teacher). Gods and demons can both be situated and worshipped simultaneously in this beautiful land at whose center is this inexplicable contradiction.

The second dichotomy lies around the expression of feminine form. On the one hand, from the sculptures of Goddess Durga in central India to those of the tribal Goddess Lajja Gauri in southern India, an emphasis is laid on particular parts of the body. This does not mean that historically Indian women were highly self-conscious. Neither does it convey that they molded themselves around the masculine fascination for satisfying carnal desires. Rather, it is as if the sculptor deliberately focussed on those body parts to express his art more seductively. Many times the goddess is portrayed as being engaged in dancing or playing a musical instrument. This is different from the representation of Mary and female saints in the West. These figures from the Christian pantheon even when nude are depicted in a kind of motherly aloofness and renunciation. On the other hand, the distance between the representation of women and their treatment in Indian society was always gargantuan and is still considerable. Indian women continue to be among the most oppressed and unsafe in the world.

The festivals of Saddangu (in Tamil Nadu), Aashirvada (in Karnataka) and Tuloni Biyah (in Assam) among others celebrate femininity in its purest form. These festivals announce into the neighborhood of the girl’s family that she has now reached the age of puberty and hence is ready for marriage. Offerings are made to the divine as well as feasts accorded to the neighbors. Contrast this with the notion that as a consequence of entering puberty, the girl becomes impure every month when she menstruates. She is not to be allowed to come nearby the gods (or the kitchen in extreme cases) during those days. Finally, it is perfectly alright for the parents to announce in the public that their daughter has now entered puberty, but imparting her sex education is considered a taboo.

In the florid fantasies of the West, India is also a land of the free expression of love and coquetry as depicted in Kamasutra and erotic sculptures at Khajuraho. This is as far as it can be from the Purdah system which for centuries forced women to be behind a veil and has only started to disappear in the last century. Absorbing from Central Asian cultures, it became a symbol of virtue for a woman to seclude herself behind a purdah. Yet, it was perfectly alright for the same woman to share and enjoy the story of Radha’s romance with Krishna.

But then, India is a strange land where those who give up power are venerated more than those who possess it; where those who misuse their power earn more respect than those who allow their authority to be flouted. Such is India, the land of many dichotomies.

Stability vs. Transformation: Caste, Congress, and Civil Services

Stability vs. Transformation: Caste, Congress, and Civil Services