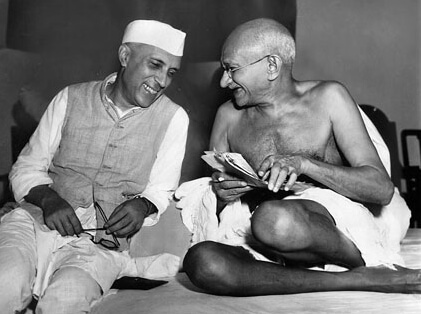

On his 55th death anniversary, here are three episodes that show Nehru’s outlook towards the opposition and which also have contemporary relevance.

In 1937, Jawaharlal Nehru was elected the President of the Congress for the third time. In the same year, an article was published in the Modern Review journal of Calcutta under the title ‘Rashtrapati’ (President) and was written by a certain Chanakya. The article brutally excoriated Nehru’s presidency as well as his demeanor. Here are some excerpts:

Rashtrapati Jawaharlal ki Jai… Watch him again. There is a great procession and tens of thousands of persons surround his car and cheer him in an ecstasy of abandonment. He stands on the seat of the car, balancing himself rather well, straight and seemingly tall, like a god, serene and unmoved by the seething multitude….Is, all this natural or the carefully thought cut trickery of the public man? Perhaps it is both and long habit has become second nature now. The most effective pose is one in which there seems to be least of posing, and Jawaharlal has learnt well to act without the paint and powder of the actor. With his seeming carelessness and insouciance, he performs on the public stage with consummate artistry…He calls himself a democrat and a socialist, and no doubt he does so in all earnestness, but every psychologist knows that the mind is ultimately a slave to the heart and logic can always be made to fit in with the desires and irrepressible urges of a person. A little twist and Jawaharlal might turn a dictator sweeping aside the paraphernalia of a slow-moving democracy. He might still use the language and slogans of democracy and socialism, but we all know how fascism has fattened on this language and then cast it away as useless lumber….Jawaharlal cannot become a fascist. And yet he has all the makings of a dictator in him—vast popularity, a strong will directed to a well-defined purpose, energy, pride, organisational capacity, ability, hardness, and, with all his love of the crowd, an intolerance of others and a certain contempt for the weak and the inefficient. His flashes of temper are well known and even when they are controlled, the curling of the lips betrays him. His over-mastering desire to get things done, to sweep away what he dislikes and build anew, will hardly brook for long the slow processes of democracy. He may keep the husk but he will see to it that it bends to his will. In normal times he would be just an efficient and successful executive, but in this revolutionary epoch, Caesarism is always at the door, and is it not possible that Jawaharlal might fancy himself as a Caesar?…. His conceit is already formidable. It must be checked. We want no Caesars.

The article was much talked about in the press. Here was a courageous writer who was criticizing Jawaharlal for not only his demeanor and conceit but also what he could become. It should also be kept in mind that this article was published after the elections of 1937 that were held under the Government of India Act 1935. Nehru was Congress’s chief campaigner in the elections and had traveled about fifty thousand miles across the subcontinent by ‘airplane, railway, automobile, motor truck, horse carriages of various kinds, bullock cart, bicycle, elephant, camel, horse, steamer, paddle-boat, canoe, and on foot.’ Congress had performed spectacularly in the elections. Patel was the fundraiser while Nehru was the star of the campaign. So, who was this anonymous writer in the Modern Review journal masking behind the title of Chanakya? Our doubts would perhaps make us think that s/he would have been either a sulking Congress worker or an adversary of the Party—someone loyal to the British, RSS, or the Muslim League. A few years later, it was revealed by a journalist that the author of that piece was ….. Jawaharlal Nehru! In a self-reflective mood and desire to not be the Congress President again due to his ideological differences with the organization at the time, Nehru was criticizing himself. He had become his own opposition and of course, this mercurial son of Gandhi didn’t become the president next year (that prodigal son of Gandhi, Subhas Bose, did). How many politicians of our nation today can exhibit this trait? Not many, I reckon.

In 1949, Rammanohar Lohia’s Socialist Party held a demonstration at the Nepalese Embassy against the takeover of Nepal by Rana. Section 144 was in effect and thus Lohia was arrested. Home Ministry came under Patel at the time and thus Nehru couldn’t do much on his own. Lohia remained in jail for over a month. Nehru wanted to show a gesture of affection towards the young Socialite and despite the fact that his own government had arrested Lohia, he sent a basket of mangoes to the jail. Patel was annoyed by this gesture and asked Nehru for a reply. Nehru could only write back meekly that personal relations should not be mixed with politics.

In 1959, Chakravarti Rajagopalachari (Rajaji) was the center of mass of the opposition in the parliament. He had come out of retirement and was directing the opposition through his Swatantra Party. There were many times when Nehru had got annoyed by Rajaji’s opposition. There were also other times when both freely shared their views with each other in the larger national interest. It so happened that Rajaji was an ardent opponent of nuclear warfare and had been taking initiatives on his own to urge both the U.S. and the Soviet Union to desist from testing nuclear weapons. In 1961, he exchanged letters with Nehru to discuss in what way he could be helpful for the cause. He had never traveled outside the subcontinent and was already eighty-three. Furthermore, he was the one man in India who had the moral courage as well as the agility to bring the opposition together. It is a no brainer that any politician in power today would have taken the call to send Rajaji as a peace activist to the Western nations in negative. But, not Nehru. Rajaji did go and went through the official support of the Gandhi Peace Foundation directed by the Government of India. Personal relations were again not to be mixed with political opposition.

That other great patriot and Gandhian Socialist, J. B. Kripalani, had once written something to the tune that Gandhi was like a shepherd and we were all like his sheep. We used to dutifully follow the shepherd and go wherever he used to lead us. There was one amongst us however who would often go astray. At such times, the Shepherd used to leave all of us to bring back the stray fellow. We would all feel jealous thinking what have we done to suffer Shepherd’s neglect. Clearly, the Shepherd priced that one sheep going stray and wanted him to be with the group at all times. I am sure you would have guessed that the lone sheep which would often go astray was Nehru. That sheep had various ideological differences with Gandhi which were expressed in the open (one only has to read his autobiography). However, the Shepherd knew (and has been proved rightly so in the past seven decades) that this sheep could do what no other could.

The foundations of the plural India that we live in were erected by Nehru. I will not mince words while saying that if he would not have been at the nation’s helm for such a long time after Patel’s untimely death in 1950, ours would have been a less plural, a less equal, a less affectionate, and a less humane society. It was he who stood as the adamantine bulwark against Communism on the Left and Hindutva on the Right. It was he who established a foreign policy which has been continued by all governments since and has been hugely successful. It was he who established the institutions of governance that have sustained the Indian democracy. It was he who showed the world that democracy can be compatible with pluralism as well as with nationalism in a poor illiterate nation. In the West, democracy had been preceded by the formation of a nation-state and absorption of the forces of the Industrial Revolution. In India, Nehru achieved the confluence of all three simultaneously.

Though as we saw above, Nehru warned that ‘We want no Caesars,’ Shakespeare has written a phrase for Julius Caesar that could be apt for Nehru: ‘Here was a Caesar! when comes such another?’ For Nehru, we may add, probably never.

And, no, today, on his death anniversary, I will not go into where he went wrong. That is not what Hinduism has taught me.

Dilip Kumar: A Synonym of Perfection

Dilip Kumar: A Synonym of Perfection