The state of any medium of cultural expression such as art, cinema, music, theater, etc. is reflected in the politics of that society. Talking about today’s nation-states, generally, the governments to the left of the political spectrum (but not too far left) support the flourishment and portrayal of new ideas while those on the right try to curb them. Sans political ideology, the other axis through which we can focus on this spectrum of freedom of cultural expression can be the dynamic between the course that the nation is taking due to the government’s policies and its public perception. As an example, this connection is easily observable in how Indian cinema, especially Bollywood, evolved in the past eighty years.

In the last three decades of British India, cinema was evolving around the world as a new medium of expression particularly to visually narrate folklores and popular stories. Some novel breakthroughs were made in this genre such as by Charlie Chaplin to move away from the monotony of dramas. As the movies started to incorporate sound in addition to visuals, a lot more could be expressed in the same scene. Perhaps nowhere more in the world was this true as in India where songs became an essential (and inescapable) component of movies. As soon as the British rule started to fade away from the mid-1940s, a new genre of playback singers and theatre actors (like the beautiful and melodious Suraiya, the great Prithviraj Kapoor, and the impeccable Balraj Sahni) made a name for themselves into this new landscape of “commercial movies.” Cinema started to move out of the theater and descend from the realm of the rich to the general audience.

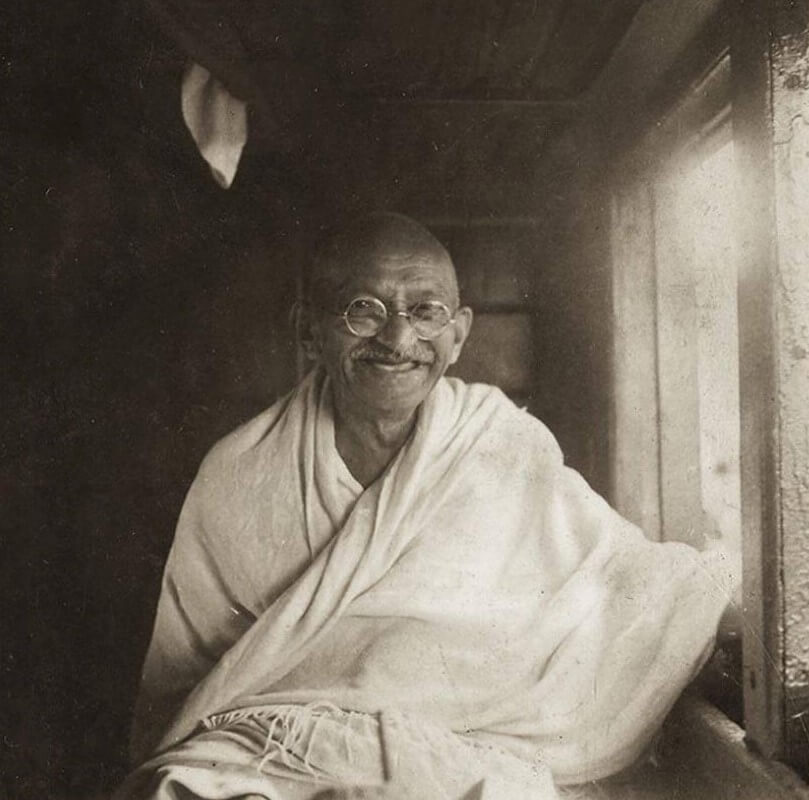

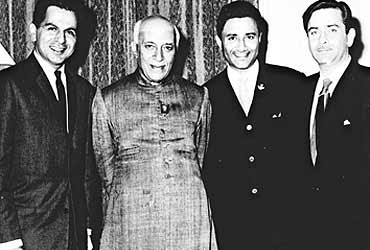

As India became free from the British yoke, cinema started to flourish much more freely. There was a lot of idealism in the air to build a new nation based on Gandhian principles. This idealism combined with Nehru’s majestic and inspiring personality fueled optimism in the society. It was like out of a bolt of lightning from the sky that came out the best actors (the perfectionist Dilip Kumar, the evergreen-romantic Dev Anand, the showman Raj Kapoor, the neck-curving-wild-dancing Shammi Kapoor, the beauty-queen Madhubala, the tragedy-queen Meena Kumari, the natural artist Nutan, the versatile Waheeda Rehman), playback singers (the virtuoso Mohammed Rafi, the melodious Kishore Kumar, the echoing Mukesh, the nightingale Lata Mangeshkar, the playful Asha Bhonsale), directors (the legendary Satyajit Ray, the phenomenal Bimal Roy, the facetious Vijay Anand), the lyricists (the sophisticated Majrooh Sultanpuri, the multi-faceted Sahir Ludhianvi) and the music directors (the towering S. D. Burman, the innovative Salil Chowdhary). There are literally hundreds of more virtuosos that I can add to the above list like Hemant Kumar, Kaifi Azmi, Talat Mehmood, Ashok Kumar, Manoj Kumar, Rajendra Kapoor, Dharmendra, Sadhna, Mala Sinha, but I hope you got the point. Without a shadow of a doubt, any lover of cinema will tell that the 50s and 60s were the golden years of Indian cinema. As Indians started to believe in the possibility of a prosperous future and democratic forces started to seep in through the countryside during this time, viewership of the work of these legendary artists increased by many folds. Thus, the movies between 1950-1965 showed a great deal of creativity in every single department. To state it simply, the efforts around socio-economic advancement in the Nehru years were reflected in the cinematic space as well.

With Nehru’s death in 1964, the war with Pakistan in 1965, food shortages of the mid-1960s, and the succession crisis after Lal Bahadur Shastri’s death, India started to lose confidence in itself. Gone too were the high days of creativity in Bollywood. Slowly, by 1970, movies like Baiju Bawra, Mughal-e-Azam, Madhumati, Guide, Mother India gave way to the Rajesh Khanna’s emotional-and-dramatic-romance era. Subsequently, Indira Gandhi’s authoritarianism and disastrous “Socialist” policies which fueled corruption and social unrest inaugurated the era of Amitabh Bachhan’s Vijay-the-angry-young-man persona. Of course, there were some honorable exceptions to this trend such as the movies directed by the fastidious Hrishikesh Mukherjee and M. S. Sathyu’s Garm Hawa. However, by and large, the 70s was a decade when the audience loved to watch cinema purely for the satisfaction of their materialistic desires: (excessively)emotional fight-the-villain-win-the-girl dramas and angry-upstart-fighting-the-system-making-it-big masala movies.

Due to the upheaval created by the Emergency and the instability in the government after its withdrawal, the Congress Party started to lose its hegemony. The decline in the fortunes of Congress brought sunshine to the prospects of various regional parties. This sudden devolution of power combined with Indira Gandhi’s disastrous economic policies from previous years was a sure recipe for disaster. Thus, by any reckoning, the 80s was the worst decade in post-Independent India. The economy was moving toward a huge crisis while multiple secessionist movements had to be dealt with at the same time. India had lost all optimism and confidence in itself. The movies and songs from the commercial cinema of the 1980s are best left alone (well, they do accompany you in public transport in U.P.). Thankfully, the void created by mainstream movies started to get filled by regional and alternative cinema. This was when Javed Akhtar, Shabana Azmi, Gulzar, Naseeruddin Shah, Om Puri, Sai Paranjape, and others started to come into their own. As the appeal of movies with intricate plots, all set in Bombay faded, it gave way to much simpler storylines shot around the issues faced by commoners.

With the economic liberalization of India in 1991, a new era in cinema emerged. Foreign brands and clothing made their way into movies while the movie industry started to look more than ever before towards exotic locations in Europe for filming (imagine any song with Shahrukh Khan in it and reflect on where does he stand and what does he wear). As the middle-class slowly became more secure, romance returned into their lives and out came the trio of Khans in Bollywood. Movies became a curious mixture of the East and West, at home everywhere, out the place nowhere. Except for the crisis in Kashmir, as tempers cooled in other parts of India, the stories started to come out of the Hindi heartland and reflect India’s diversity by freely incorporating characters from various parts of India. This was such a big change that one might say, the history of Indian cinema can be divided into the pre- and post-1990 era.

In the 2000s, the process from the previous decade continued and went many steps further. As relations between India and the United States normalized, the U.S. (especially New York) became a prime destination for filming movie sequences or sometimes the whole movie (Kal Ho Na Ho, My Name is Khan, Dostana, etc.). The culture of sequels and remakes which was already flourishing in Hollywood was absorbed by Bollywood and many franchises made their first appearance. As the two nations came closer, quintessential Hollywood movies blended for Indian audiences also made their appearance (Dil Chahta Hai, Taare Zameen Par, Koi Mil Gaya, etc.). For the first time in the history of commercial cinema, nudity and physical expression of love became commonplace and acceptable (Murder, Kalyug, Jism, etc.). Finally, with the rapid expansion of the economic pie under UPA-I, as the youngsters from small cities started to dream big, Bollywood started to leave Mumbai’s glittering streets and come to their doorstep (Swades, Omkara, Gulaal, Gangaajal, Dabangg, etc.). This last transformation is still rapidly undergoing. More than ever, now we see so many movies the storylines in which are based outside the main metropolises (Masaan, Dangal, Gangs of Wasseypur, Kai Po Che!, Tanu Weds Manu, etc.)

Above, I have only provided an overview of the general trend between cinema and politics in India. For every decade discussed above, there can be many exceptions (I can myself point out some of them as well). Irrespectively, the general trend holds true: the politics of a nation has a large role to play in its socio-economic development which is directly reflected in its cultural expressionism (such as the contrast between Western Europe and the Middle East when it comes to cinematography). A Kurdish proverb says: If two fish fight in the ocean, the British have something to do with it. Similarly, if traditional forms of cultural expressionism are not flourishing in a nation and are struggling with censors and adverse public perception, maybe it’s time to look around and question the leadership of the nation.

(Dis)United and (Un)Progressive India

(Dis)United and (Un)Progressive India