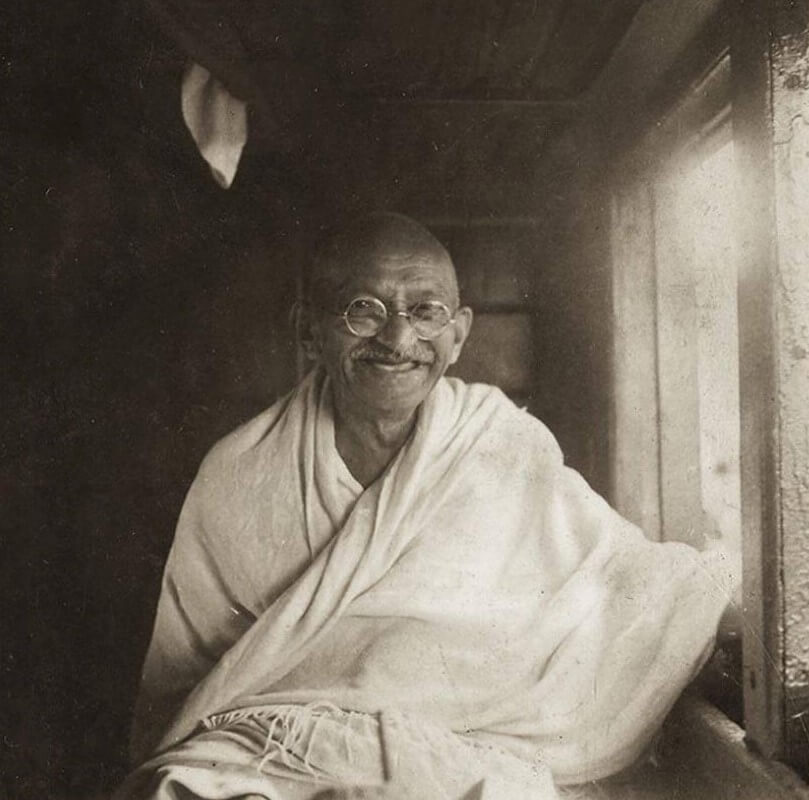

How to introduce Gandhi to somebody who knows not much about him? In fact, how to interpret Gandhi oneself? It’s interesting to think that he seems to be so approachable and yet so distant. His innocent childish welcoming smile radiates happiness and warmth all around and yet there is a sense of impermanence about him that elevates him above our worldly realm. It is so easy to relate to him as a human being embodying all human failings and yet, at the same time, he is revered as a Mahatma—inscrutable and mystical.

What did Gandhi represent? For the British, he was the foremost opponent of Imperialism. For Hindu extremists, he was the chief appeaser of Muslims. For many Muslims, he was an opportunistic Hindu who partitioned the nation. For caste Hindus, he was a misguided dissenter who challenged an age-old golden tradition. For Dalits, he was an apologetic caste Hindu. For Communists, he was a god-loving imposter funded by capitalists. For capitalists, he was a socialist who believed in the virtue of village republics. For materialists, he was everything that is wrong with asceticism. For ascetics, he was a fake fakir who dabbled into politics. It seems like every community has its own grievances against him. They disagree with him, debate with him, decry his legacy, yet cannot disregard him.

Gandhi never preached violence (in fact was the greatest apostle of non-violence since Buddha), practiced no chicanery, and had no curtain between his personal and public life. More than any other public figure of the twentieth century (or the modern era), Gandhi’s life is in the public domain. Everything about him—dietary habits, blood pressure, frequency of nature’s call, public appointments, travel engagements, idiosyncrasies—was carefully recorded, compiled, written on, and published. What more? He even used to himself tell the British exactly what, where, and how he would do—launching the non-cooperation movement, breaking the salt law, going on a hunger strike—to protest against them! Want more? He wrote himself on the harsh way he treated his wife when they were young, on the issues he faced with his oldest son, and the guilt he felt when one night, he had an involuntary semen discharge after having taken the vow of celibacy. Both his public and private lives (if it is at all possible to separate them) were an epitome of truth and renunciation. He lived by what he preached. The charm of assuming public office never corrupted him. As early as 1931, he had declared that should India be independent during his lifetime (to which he looked forward eagerly), the highest public offices “will be reserved for younger minds and stouter hearts.” Furthermore, he did more than any other caste-Hindu of his generation for the emancipation of the Untouchables.

Was Gandhi racist? A big debate has been undergoing from the past few years about this. Unequivocally, Gandhi of the early 1890s was racist. He wrote pejoratively about blacks in South Africa as “Kaffirs” and followed social taboos associated with discrimination against them to some extent. He did not raise his voice for them in the same manner as he did for his fellow Indians. Yet, gradually with time, his views color and race evolved. By the 1930s, he conversed with and became an inspiration to African Americans in their own fight against racial segregation. Not just on race, Gandhi’s views on religion, caste, language, nationalism, internationalism, humanism, and pretty much everything else evolved with time. What mattered to him was that if he never made any “hobgoblin of consistency,” that if he was true to himself “from moment to moment,” he did not “mind all the inconsistencies that may be flung” on his face.

In recent times, a new tradition has taken root, that of re-evaluating and re-re-evaluating the legacy of historical figures based on our contemporary sense of modernity and justice. Many public figures (Mohandas Gandhi, Nelson Mandela, Martin Luther King Jr., Jawaharlal Nehru to name a few) have fallen prey to this tradition across the world and have crashed from the high sky to the netherworld. This is nothing but injustice to them. Nobody from the past should be left alone, everybody must be re-evaluated but this should be done without agendas. Else, how many historical figures from any part of the world will pass the contemporary test of liberalism when it comes to LGBT values? Perhaps not a single one. Yet, this should not diminish their legacy since they were simply products of the times they lived in.

Gandhi had repeatedly expressed the wish and was confident about living to the grand old age of 125. This is because, apparently, Krishna had lived to that age. Until 1945, Gandhi the septuagenarian was very healthy and high in spirits. By January 1948, he was looking at death everywhere in front of himself. The Hindu-Muslim riots of 1946 and after Partition had disheartened him and killed his will to remain alive. Frail and teetering, he went on the greatest marches of his life in rural Bengal (traversing mosquito-infested forests by walking and staying for nights in Hindus’ homes) to stop the communal madness and saved thousands of Hindus. Staking his own life many times, he preached peace and unity to frenzied members from both communities. When all else failed, he went on fasts unto death to pour sense into the minds of humans turned communal beasts. Magically, such was Gandhi’s hold on the masses that his threat to starve himself to death unless they stop all rioting used to work. When the time came, he did the same in Delhi, this time to save Muslims. All his life, Gandhi had preached Hindu-Muslim unity and in the end, he died for the same. As the Mahatma died, this supreme act of sacrifice materialized what was probably his last wish. All violence in Delhi and elsewhere stopped. All communal madness ended. Everybody was subsumed in grief and helplessness. Everybody felt like an orphan. Every eye became wet. Every spirit, anguished. As the conclusion to this writeup, let me just repeat the oft-quoted line that Einstein wrote for the Mahatma: “Generations to come, it may well be, will scarce believe that such a man as this one ever in flesh and blood walked upon this Earth.”

Parallels between Cinema and Politics in India

Parallels between Cinema and Politics in India