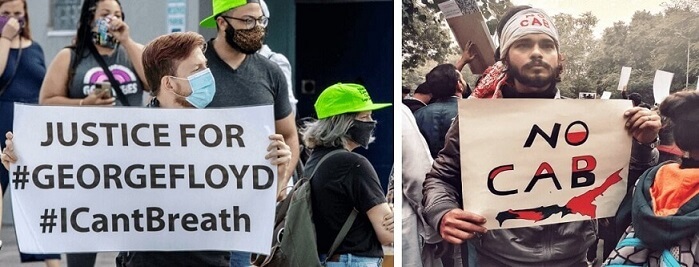

In addition to the mortal and economic havoc wrought by the epidemiological pandemic, COVID-19, among other devastating events like cyclones, wildfires, locust attack, etc. that have so far characterized the year 2020, two more developments this year brought renewed focus on minority groups in world’s largest democracies, India and the United States. I allude, of course, to the passage of the Constituent Amendment Bill in December 2019 in India and subsequent protests that continued in January and February 2020 and the killing of George Floyd with accompanying mass protests in America.

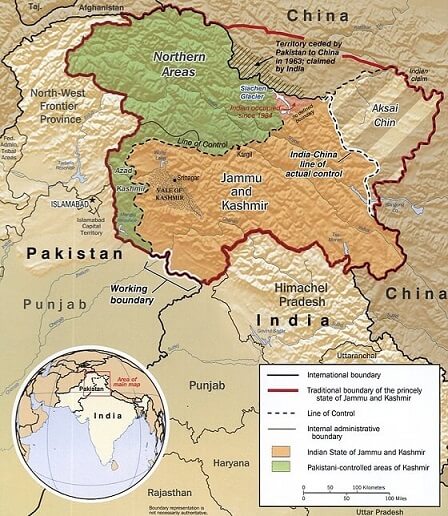

In both cases, the developments that culminated in mass protests (a part of which turned violent) are embodiments of long-standing institutional discrimination against the respective minority groups. As a rule of thumb, in India, four types of minority/social groups have always been discriminated against and their quality of life is lower than other Indians: Dalits, Tribals, Muslims, and Women (the exception is the Kashmir Valley where Hindus should also be included in the list). As another general rule, in America, four minority/social groups have always been discriminated against: African Americans, Native Americans, Blue-collared Immigrants, and Women. Among these demographic groups, let us here focus on the similarities and differences between African Americans and Indian Muslims.

As per the 2010 census, multiracial African Americans constitute 14% of the U.S. population while as per the 2011 census, Muslims constitute 14.2% of India’s population. While the aggregate numbers of the two social groups would have a vast difference, in terms of the composition of the population, both of these groups are what can be termed as significant minorities. Yet, the paradox lies in the fact that since one in seven nationals belong to these minority groups in either nation, they can neither be ignored altogether nor are they electorally so strong in numbers to bring real change on their own in a first-past-the-post electoral system. Even with this handicap, the U.S. was able to elect its first black president in 2008 but India’s parliamentary democracy makes it even harder to elect a Muslim prime minister.

However, electing a figurehead from the minority group does not in itself bring about a sea change in its condition. The institutional discrimination that these minority groups undergo is evident from various statistics like literacy rate, higher education attainment rate, income level, health disparities, crime rate, etc. On each and every one of them, African Americans and Indian Muslims perform worse than their other national brethren (as shown by various studies conducted by American Universities and by the Sachar Committee Report in India). Even without talking about statistical data, it is easy to perceive (if one really wants to) the day to day discrimination against these minority groups: ghettoization; police brutality; sexual, ethnic, or religious innuendos. It is not that others consciously partake in belittling these minorities or in objectifying them. Rather, doing so has entered the arteries of society in both nations.

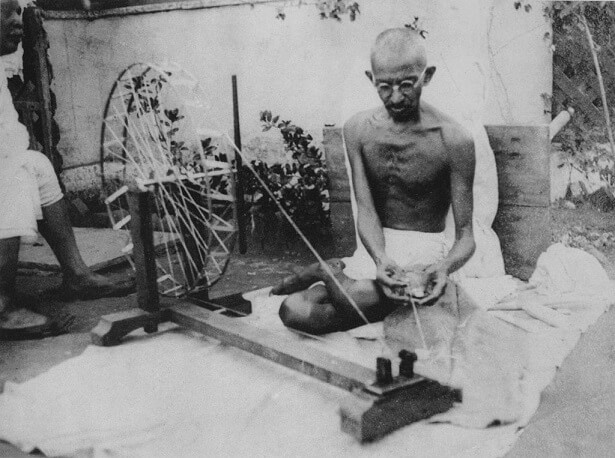

While the above can be true for various minority groups in many nations, a few factors make these two minorities distinctive: respect for Gandhi and (by and large) non-violent methods (exemplified by Martin Luther King Jr. in America), significant contributions toward art and culture (Hollywood, Bollywood, Jazz, Indian Classical Music, etc.) in which these groups punch way above their demographical weight, and acute political awareness leading to vibrant dissenting culture.

However, the similarities end here. Except for the obvious fact that race is the distinguishing characteristic for one minority group and religion for the other, there are chiefly three differences between the two minorities. First, it is a universal truth that untold atrocities were committed against the forefathers of today’s African Americans. The devastating tales of the slave trade and slavery have rightly inculcated a general feeling of shame, guilt, and remorse among whites in America. This is altogether opposite of the mainstream perception that with Islam came violent looters and invaders to India. In this way, while the history of one minority brings a feeling of being wronged against by the majority, the history of another brings a feeling of righting the wrongs done to the majority by the minority.

Second, as a consequence of the first, White Americans are wholly aware that their own forefathers planted the African race in North America while visible differences between the two races make it very clear. As a result, the sense of unfinished business, sort of a national purpose, is evident by which the assimilation of African Americans by giving them equal rights and opportunities is considered the right thing to do. On the contrary, in India, there are few visible differences between Hindus and Muslims who often look the same, eat the same food, speak the same language, dress in the same manner, and listen to the same music. However, Hindus perceive Indian Muslims (not wrongly) mostly as converts while the zealous among the former harbor the feeling that the latter should be converted back to Hinduism (thus the so-called Ghar Wapsi campaigns).

Third, as a consequence of the above two, across the political spectrum (though unevenly) in America, there is an acceptance that something should be done for the betterment of African Americans. As a consequence, they benefit from various schemes, probably the most notable among them being that of affirmative action. On the contrary, in India, Muslims are not generally the recipients of reservation in education and jobs aimed at the upliftment of minority social groups that are or have been historically discriminated against.

Yet, there is a lot to be optimistic about for both of these minorities. Their quality of life in every aspect has constantly been improving from decades past and new young leaders continue to come out from both communities in various fields. Spontaneous protests without centralized leadership or overt backing of political parties in both nations have once again shown that these minority communities are ever-ready to defend their rights and demand equality from any ruling dispensation. These minority groups should keep faith in the democratic systems of the world’s largest democracies while the governments should keep faith in the loyalty to the constitution shown by them. Faith, after all, as Tagore wrote, is the bird that feels the light and sings when the dawn is still dark.

Cities, Big Business, Entrepreneurs: Mahatma Abhorred Them and We are Paying Today

Cities, Big Business, Entrepreneurs: Mahatma Abhorred Them and We are Paying Today