There have been many great men and women whose contributions to contemporary Indian society are evident in our day-to-day lives. Buddha, Mahavira, Ashoka, Adi Shankaracharya, Kabir, Guru Nanak, Akbar, Savitribai Phule, Mohandas Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, Mother Teresa, are just a few of the names of those revered souls whose thoughts and actions still pervade the society—like a subterranean river flowing beneath the rocks but crucial to the existence of the whole landscape.

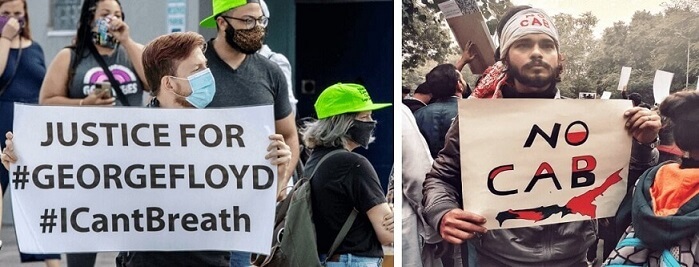

Among the names I mentioned above, perhaps Gandhi’s contributions are today the most tangible since it has only been seventy-two years since his death and also because our constitution, politics, economics, and social lives are still dictated to a large extent by his views and actions. Every major debate and policy decisions in our nation—foreign policy, Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), poverty alleviation, healthcare, education, economic agenda—are still formulated in his name or take inspiration from his ideas or both sides of the debate use his views to bolster their own arguments. Perhaps it was altogether logical then that while announcing Gandhi’s death to the nation over a radio broadcast on that fateful evening, Nehru had remarked: ‘The light has gone out of our lives and there is darkness everywhere…. The light has gone out, I said, and yet I was wrong. For the light that shone in this country was no ordinary light. The light that has illumined this country for these many years will illumine this country for many more years, and a thousand years later, that light will be seen in this country and the world will see it and it will give solace to innumerable hearts.’

Felicitations aside for undoubtedly the greatest human being of the twentieth century, this writeup is about how Gandhi’s views have been adopted rigidly by our leaders and society to the detriment of the nation.

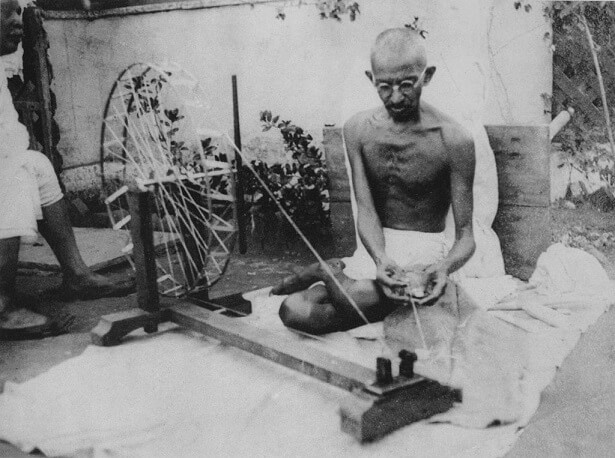

For most of his political life, Gandhi held deep-rooted respect for the village life and small-scale industries. This was at a time when across the industrial world, scores of people were migrating from villages to cities, and from agriculture to other occupations. Gandhi idealized village life and fantasized self-sufficient village republics across India. The rise of cities was looked at with suspicion by Gandhi: ‘To me the rise of cities like Calcutta and Bombay is a matter of sorrow rather than congratulation. India has lost in having broken up a part of her village system.’ Gandhi’s ideas of self-reliance went even further: ‘My own view is that evils are inherent in industrialism, and no amount of socialization can eradicate them.’ He insisted that ‘India’s salvation consists in unlearning what she learnt during the last fifty years. The railways, telegraphs, hospitals, lawyers, doctors, and such-like have all to go,’ Such a model would of course not have created a strong, self-reliant, and modern twentieth-century nation-state.

Gandhi’s idealization of village life and small industries helped to strengthen the roots of the freedom movement by making it a mass movement in which everyone could participate. But, it was also sort of ironical on two accounts. First, until Gandhi’s return from South Africa in 1915 when he began to travel across India (refraining from political activities to fulfill the promise that he had made to his political mentor, Gokhale), he had probably never spent a single night in an Indian village—Gandhi’s fascination until then was thus with a version of village life that was the conception of his own mind. Second, while Gandhi first constructed the Sabarmati Ashram and later the Sevagram Ashram and led a simple life, to sustain the basic needs of his life and ashramas, he relied heavily on big business—Sarabhai, Birla, Bajaj, among others, were close associates and contributors. It is because of this lifestyle that Sarojini Naidu had once asked him ‘Do you know how much it costs every day to keep you in poverty?’ Gandhi’s response is undocumented or perhaps he chose not to respond since he was aware of his limitations.

Fortunately, being self-aware of these limitations and the rigidity of his views, Gandhi chose Nehru as his successor despite knowing that the latter stood totally at odds with his socio-economic views.

It seems that Gandhi’s idealization of simple village life and respect for the virtuous lives of the poor have been perennially adopted by our politicians across all parties. On the contrary, the fact of the matter is that across the nation, people are migrating from villages to urban centers in search of better livelihood for themselves and their children (a case in point being so many hundreds of thousands of laborers returning to their villages these days due to the COVID-19 pandemic). This is not a phenomenon specific to India. Developed nations have only about 1-3% of the total population employed in the agricultural sector compared to almost 50% for India. The agricultural sector in India contributes only 15.4% of the total GDP but since it employs the most people, by far, the politicians rely heavily on this vote bank. The disgust shown by the politicians toward cities (just like Gandhi did) is also evident in the decaying state of our urban centers (slums, pollution, lack of potable water, etc.) which cannot by themselves sustain such a large number of people migrating from rural India. The tragedy of our system is that erecting new cities is also considered anathema since it by its very nature requires collaborating with big business (another “devil”) and takes away the vote bank lying in our villages.

Four years ago, Modi Government had set the ambitious target of doubling farmers’ income by 2022. While it is now impossible to do so due to COVID-19, it was not possible to do it anyway without a) diversifying the sources of income of farmers (beekeeping, floriculture, sericulture, small-scale industries competing with Chinese goods, etc.) thus reducing their dependency on agriculture, b) reducing the total number of farmers to get rid of the ever-decreasing size of landholding by framing policies to incentivize further migration to urban settlements, and c) developing new urban settlements to accommodate people coming from rural India. On all three accounts, the government failed. And, not just this government, the report card of the ten years of the UPA was similar on these three accounts.

The history of the twentieth century provides the lesson that India cannot become a developed nation while a large section of its population continues to rely on agriculture. With the adverse effects of climate change surfacing rapidly (irregularity of weather patterns, groundwater depletion, higher temperatures, etc.), the situation will only worsen. India’s cities are already operating well beyond their capacity. Only collaboration between government and big business can help in improving the infrastructure of our cities and building new cities. Alas, cohabiting with big business is a big no-no. In the Indian moral scheme of things, the dream of becoming a successful billionaire entrepreneur with the resources to transform millions of lives is situated much below than being a part-time Gandhian social worker in a remote village.

One might ask why the rich are portrayed as evil in India? The answer lies in the famous saying that the fundamental DNA of Indian politics is Socialist. Before the economic reforms of 1991, the Socialist license-quota-permit raj generally mandated unhealthy collusion between government and big business with the latter usually circumnavigating the system through unfair means. Some of the fallout of that system is still present in today’s policies. Liberalization has changed much in India, for the better, but the statist mindset of the politicians is yet to be changed. Gandhi could not foresee a time when the fast-developing world would necessitate the acceptance of a changed lifestyle—one that is in a sense very different from that of rural India.

One could sometimes disagree with the Mahatma but could always be sure that he would speak out his mind freely. Today, do we have any politician of some repute who can openly proclaim that the salvation of rural India lies not in binding it to agriculture but rather creating more opportunities for it in villages and by erecting new urban settlements? Personally, I have not seen any.

Central Vista Redevelopment Project: An Exercise in Self-Love, Deception, and Vanity

Central Vista Redevelopment Project: An Exercise in Self-Love, Deception, and Vanity