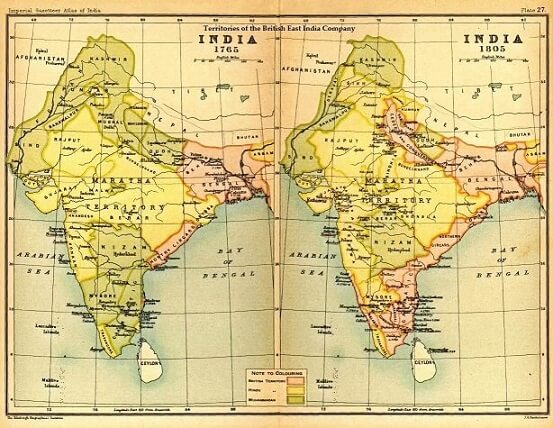

Time and again, Bengal has given the world remarkable personalities in every field of human endeavor. Perhaps no other part of the subcontinent has so consistently produced so many remarkable figures. In the nineteenth century, great social reformers like Raja Ram Mohan Roy and Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar transformed not just Bengal but they also had a great impact on Indian society. Swami Vivekananda placed India proudly and firmly on the world stage with his lecture tours on Hinduism, Advaita philosophy, Vedanta, and Yoga. Subsequently, the first part of the twentieth century was dominated by the forceful personalities of Rabindranath Tagore and Subhas Chandra Bose. During the same time, the Bengali Bhadralok could never forget and forgive the eccentric Gujarati who suddenly emerged as the leader of the freedom movement. This came as a shock to them since the earliest and most dominant voice against the British-rule had emerged from Bengal in 1905 when the province was about to be partitioned. Bengal continued to have a complex relationship with Gandhi because of the latter’s dynamics with C. R. Das and Subhas Bose.

When Partition came, Gandhi wept with Bengal. He chose to spend days while traveling in Noakhali, staking his own life, to apply the balm of love on the wounds of Partition. Perhaps Bengalis wondered that now after Independence, they will get their rightful place in Indian polity. Alas, Subhas had died in a plane crash and the imaginative Gujarati designated a flamboyant Hindiwallah as his successor. Bengali Bhadralok felt deceived once more. Yet, the province continued to produce remarkable figures on both sides of the border. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman (voted as the greatest Bengali in a BBC poll) dominated the political space on the other side of the border while the Communist colossal Jyoti Basu established an almost-unbreachable fort on the Indian side. More recently the Nobel laureates Amartya Sen and Abhijit Banerjee are living testimony of Bengal’s intellectual tradition.

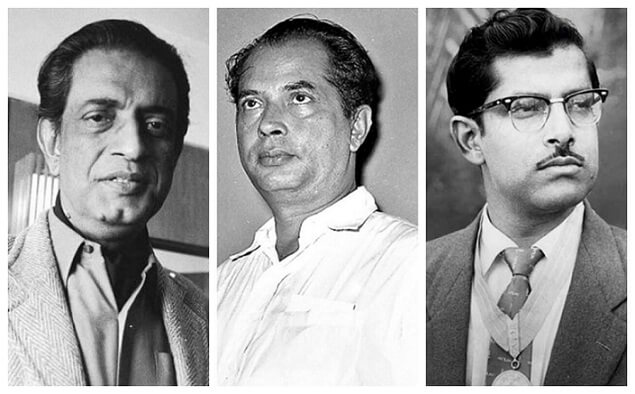

Amidst all these great personalities, Bengal’s contribution to the Indian cinema is sometimes overlooked—notice the pattern from above—or is restricted to the discussion around the maestro, Satyajit Ray. However, I argue that in the second half of the twentieth century, there existed a trinity of filmmakers hailing from Bengal who collectively changed the face of Indian Cinema: Satyajit Ray, Bimal Roy, and Hrishikesh Mukherjee.

Satyajit Ray, the maestro, inspired two generations of filmmakers in India as well as the West. His work was praised by and influenced some of the greatest filmmakers in the world—Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, Cristopher Nolan, among others. Ray was a polymath. He was also an accomplished novelist and painter. It is a tragedy for the general audience that most of his work is in the Bengali language and thus has not as widely appreciated as it would have been in Hindi or English. Irrespectively, anyone who has watched Shatranj Ke Khiladi can only marvel at Ray’s screenplay and direction. Then, there is Ray’s Pather Panchali, often featuring in the lists compiling the greatest movies ever made. One has to watch this movie to understand the realism in cinema on the lines of Vittorio De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves—another classic in the history of cinema—which had inspired Ray to become a filmmaker. Among the names of the thousands of filmmakers that the human history has witnessed, Ray’s name shines and shines radiantly, on the top of the highest mountain, alongside a select few.

Bimal Roy, who was also influenced by Vittorio De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves, made his own adaptation of the same in the Indian context, Do Bigha Zamin. And, what an absolute classic it is. Rarely has a movie so perceptively brought forward the misery of the multitude. Roy knew perhaps more than anyone else in Bollywood about bringing out the best from his actors. Whether it is Balraj Sahni’s portrayal of the farmer Shambu Mahato, or Nutan’s portrayal of Kalyani in Bandini, with Roy these greatest among actors gave some of the best performances of their careers. The poignant scene in Bandini with a bottle of poison in front of Kalyani interposed with scenes from a blacksmith hammering down on the metal must be among the greatest movie scenes of all time. Roy also made Devdas with Dilip Kumar and it remains the best cinematic adaptation of the novel by far among all filmmakers who have tried from time to time. With the perfectionist, Dilip Kumar, the rare beauty, Suchitra Sen, and the multi-talented gorgeous, Vyjayanthimala, every scene, every dialogue, every expression on actors’ faces, come out perfectly. But, Roy’s work was not just limited to good-old tragedy and misery. He also made that great masterpiece of love and romance—Madhumati—that went on to win nine Filmfare awards, a record that held for thirty-seven years. Anyone just has to watch Dil Tadap Ke or Aa Jaa Re Pardesi songs to know what made Bimal Roy the master of realism, direction, and camera placement.

Just like his movies which were so quaint and yet so very extraordinary, maybe the less said about Hrishi-da, the better. IMDb’s list of top-rated Indian movies features his Anand in the first place. I challenge anyone not to cry while watching this great gem, even if you have watched it a dozen times. The characters of Anand and Babu Moshai come alive in front of the audience in a very subtle manner. Slowly, by itself, like magic, you start relating to them, sympathizing with them, laughing and crying with them. But, Hrishi-da had a lot more to offer than just this sorrowful drama. He also directed two of the most hilarious movies that I have ever seen—Golmaal and Chupke Chupke. It was somehow so easy for Hrishi-da to engage the audience in a very simple comedic plot with no great surprises, no vulgarity, no out of the ordinary facial expressions, and yet creating amusing moments. He could make one laugh as much as cry. Furthermore, Hrishi-da also made movies tackling some very sensitive topics like misogyny, rape, and illegitimacy of a child. “What Bengal thinks today, India thinks tomorrow,” Gokhale had remarked once. Abhimaan and Satyakaam bear witness to the fact that Hrishi-da was far ahead of his time.

The above in a few sentences is a very short description of the outstanding work done by these three filmmakers which does no justice to them. What was peculiar about the work of this trinity was that their movies fitted between parallel and commercial landscapes very harmoniously. Just like most great filmmakers, they made a very selected number of movies for us to marvel at. We are still amazed by the intricacies of their work and the Indian Cinema is still learning from them. The Bengali Bhadralok is absolutely right to grudge about Bengal not getting its due in Cinema because a certain metropolis at the opposite end of the country hijacked Bangal’s heroes and made them its own. Yet, the light radiated by this Bengali triumvirate still illuminates the world and shall do so forever. One wonders if it had something to do with the Bengali society of the twentieth century and its intellectual tradition. To misquote Alexander Pope’s remark about Isaac Newton:

Cinema and Cinema’s beauty lay hid in night

God said, Let Bengalis be! and all was light.

Whither India?

Whither India?