About a year ago, I wrote about two agendas that I believed should be on the wishlist of Indian Democracy. These were the dilution of the parliamentary whip system and the emergence of a progressive pan-Indian political party with a strong Muslim voter base. While none of these two are any closer to being realized, here I am, adding another agenda to my wishlist: the emergence of political parties propagating free-market economics.

Free-market economics is nothing but to let the invisible hand of the market take its course. The market is always the true judge of the actual price of any commodity. Lest one forget, the free-market economics always triumphs in the end. If a commodity is artificially made too costly by the government (such as by pricing imports, eliminating competition, enforcing a cap on production, etc.), a black market is created and consumers start trading the commodity there at the actual rate dictated by the market (though the black market in this case). On the other hand, if the government artificially lowers the price of a commodity such as by buying agricultural products from the farmers and starts distributing it at a cheaper rate to the people, it takes little time before people start selling it in the black market to make money out of the largesse. In both cases, the government’s treasury and as an extension, the nation, loses.

Swatantra Party whose main leader was C. Rajagopalachari was India’s first and only political party promoting free-market economics. In its short life, that political party had emerged as a bulwark of opposition against Jawaharlal Nehru’s socialist approach to the Indian economy. Swatantra Party not only opposed Nehru in the press but because of Rajaji’s weight, it forced Nehru to actively engage with its leaders in public debates on economic issues. Furthermore, even before its electoral debut, Rajaji and his clique were able to pressure Nehru to abandon the potentially dangerous collective farming scheme that the Congress was planning to launch. Unfortunately, since the death of the Swatantra Party by the end of the 1960s and Indira Gandhi’s decidedly socialist turn, no political party espousing free-market economics has gathered space in India.

It is an oft-quoted sentiment that India’s fundamental DNA is socialist. There is no denying the fact that Indians are generally very idealistic. The dream of the creation of an ideal society (Ram-Rajya) pervades every political party. The idealization of the poor, romanticization of poverty, and abhorrence toward big business can be seen everywhere from our movies to people discussing politics in the roadside tea stalls. No politician in India can survive the turbulent waters unless s/he pays tribute to socialism and appear to maintain a healthy distance from the rich. Never mind that big business contribute more toward the nation’s growth and development through taxes, technology, employment, and soft power. Also never mind that all political parties are heavily funded by the rich too.

This has been the constant misfortune of Indian politics. No leader, not even as strong as Narendra Modi whose image as the Chief Minister of Gujarat was of being business-friendly, could fully unleash the forces of the free-market in India. As a result, the state has its hands in everything and they are ever-full. From the artificial pricing of agricultural products to unnecessary subsidies to banning imports from other nations instead of letting Indian firms compete against them, the Indian state presents a bad example of economic freedom. This, in a country, whose rise as a global power practically started after the economic reforms in 1991. Three decades of economic reforms have still not convinced our politicians to accept the free-market as their economic ideology. Perhaps this is also because most of the influential politicians in all parties are too old i.e. they lived their childhood and adulthood in the pre-market era. Today, it has become a folly in our democracy to be politically liberal and economically right.

How wonderful it would be if the farmers would have the option of selling their produce directly in the market wherever they want in the nation. How much more useful it would be if instead of carrying forward almost a thousand subsidy schemes, the government could empower the poor by direct cash transfer and let them decide what they want to spend on. Data across the world has shown that the latter system is much more beneficial for the needy as well as for the economy.

If we take a bird’s-eye view of the Indian political spectrum we see that most of the political parties are based on a religious/cultural/caste-based ideology (Hindutva in the case of Bharatiya Janata Party, caste-centered in the case of Bahujan Samajwadi Party, or regionalism in the case of various state parties such as the Telugu Desam Party). On the other hand, parties like the Indian National Congress seem to be confused between promoting socialism (which they vocally advocate and many times materialize to their own torment) and advocating for free-market reforms. There is no clear ideological division in India based on the economic divide between the political parties. Every political party has to appear socialist and do reforms by stealth while claiming credit years after the deed was done for public benefit! Fake socialism is an issue of consensus across the political lines, whether leaders publicly agree to it or not.

The twentieth-century was two decades back while the fall of the Soviet Union occurred three decades back. The era of Communism and blind Socialism is behind the world. Today, It is one thing to design schemes for the benefit of the poor and entirely different to dictate the economic pricing of various commodities or artificially creating walls to hamper competition. The governments should quit being the keepers of the self-interest of the poor. When two people trade with each other, both of them profit, and at the same time, the activity of trading is such that the sum is more than the constituents. For example, if a baker trades with a carpenter for a cricket bat from a carpenter, not only does she has a cricket bat now which she did not have earlier but she also has a chance now of becoming an international cricketer. Free-market trading creates new opportunities.

The father of modern economics, Adam Smith has written that “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner but from their regard to their own interest.” Instead of assuming that it knows how the farmer can best flourish, how the businessman can best contribute to the nation, how a university can best attract bright students, the government should let the forces of the free-market reign and trust in the incentive of self-interest inherent in the consumer. One hopes that as the post-economic liberalization generation (the so-called millennials) starts coming to the fore in politics, a visible change would be seen across the political spectrum.

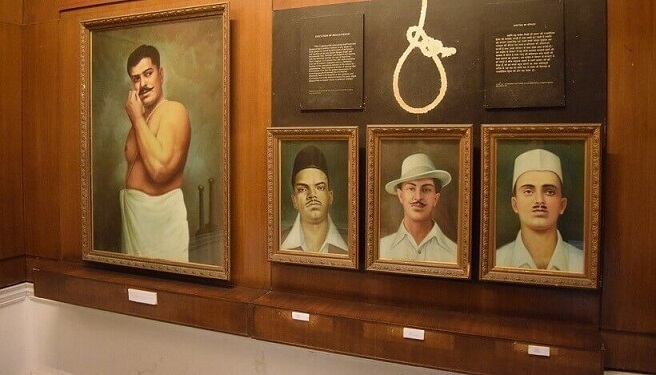

The Legacy of the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association

The Legacy of the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association