In the past seven decades, Indian democracy has matured to a level where we, Indians, can be rightly proud of our democratic achievements. Benjamin Franklin once wrote that the duty of a citizen is to question his government. Thus, I dare to propose two agendas below that should on the wish list of our democracy. Moreover, can there be a more propitious day to discuss this topic than the birth anniversary of B. R. Ambedkar, “Father of the Indian Constitution”?

The first agenda concerns the concept of the whip and its associated clause in the anti-defection law. Indian democracy borrowed the concept of the whip from the British parliament. Today, the same British parliament, as well as the U.S. Congress, do retain this practice in theory but it is avoided in practice. This provides the legislators freedom to take a line different than that of their party. This freedom not only strengthens the democratic system of the nation but also helps in flourishing inner-party democracy.

At a time when most of our political parties are run in a top-down manner either by dynasties or by “leaders elected through a consensus,” there is much India can learn from the U.S. and Britain. Ironically, in India, the political parties that actually function on democratic lines are those on the far left of the political spectrum. The current anti-defection law in India provides the right to the political parties to dismiss its legislators if they do not vote as per the party line. It is to be noted here that the anti-defection law in itself is not to be dispensed with since it provides stability to the legislature in the multi-party democracy that India is. Rather, the legislators in India should be able to secure more freedom of divulging from their party without facing consequences. It will lead to the citizens of every constituency obtaining the right to know where do its elected representatives personally stand on issues concerning them. The same parliamentarians are often seen as presenting views antithetical to those of their party when they function in parliamentary committees. This is because these committees work away from the penumbra of the media. As a consequence, these committees produce commendable reports—an example where lack of transparency can be fruitful among other cases such as in issues concerning national security and diplomacy.

Dilution of the whip system will also raise the level of debates in our legislatures as well as stimulate inner-party democracy. The present system acts as an ally for the political bosses in killing dissent from within. Dissent, lest we forget is the essence of democracy. Finally, dilution of this system may even facilitate more efficient functioning of the legislature by attenuating the pandemonium.

The second agenda may perhaps be controversial to advocate: a pan-Indian political party with which Indian Muslims can relate. Muslims in India (along with Dalits and Tribals) continue to be an oppressed minority. Whether it be factors such as the standard of living or education, Indian Muslims are a disadvantaged lot (see Sachar Committee’s report). Indian Muslims also do not have adequate representation in our political life. On one hand, the right-wing political parties do not trust Muslims and hence do not even field Muslim candidates in elections. Such parties continually pose Indian Muslims as a group which has gained an unfair advantage in the Indian democracy (despite data showing the opposite in every form), a community whose patriotism can be questioned (despite seven decades of cohabitation) and followers of a religion whose fanatics have wreaked havoc in Kashmir and many regions of the world (despite Kashmir being a political and not a social issue while Indian Muslim community continues to be an outlier in the pan-Islamic world narrative). On the other hand, to court Muslims, many political parties stroke fears of pro-Hindutva forces and present themselves as bastions of secularism. These political parties are in fact another stimulant in demonizing Muslims by advocating for their most regressive social strands.

Now, one might ask, why should religion be brought in while building a political party in a democratic secular state? There are two answers to this question. The practical answer is: after what L. K. Advani and his acolytes wrought on the Indian democracy, religion is here to stay. Gone are the days when secularism meant attempts to completely excise religion from the political discourse. Today, various political parties in India already swear allegiance to a particular religion, caste, or regional pride. Muslims in India should project their best leaders of the liberal tradition. These leaders must be ready to show a mirror to the Indian democracy as well as to their own community. Moreover, there is one factor that goes in the favor of Muslims which sets them apart from their more vocal brethren, Dalits. Taking a dig on the Caste System, the French anthropologist Louis Dumont characterized ‘Indians’ as Homo Hierarchichus. Despite multiple attempts, various gradations inside every caste have impeded the creation of a pan-Dalit or a pan-Yadav political party in India. Muslims, though share a common brotherhood and are much more likely to unite across the nation.

The theoretical answer to the question touches on the celebrated Federalist 10 essay written by “the Father of the American Constitution”, James Madison. Madison insightfully wrote how competing factions lead to stability in a republic by putting a check on each other. After partition, India lost many educated Muslim leaders. It is a tragedy that Indian politics could not produce liberal Muslim leaders (or they were lost because of populist policies as in the case of Arif Mohammad Khan). The instability of our democracy stemming from inequality and unfair treatment of minorities may yet be corrected by the emergence of a political party that adopts a settled and liberal ideology towards the Indian Muslims. Realizing the dream of democracy is a continuous process. India can become a more egalitarian democracy if 14% of its population can unite and actively compete for resources rather than waiting for the fruits of development to slowly trickle down.

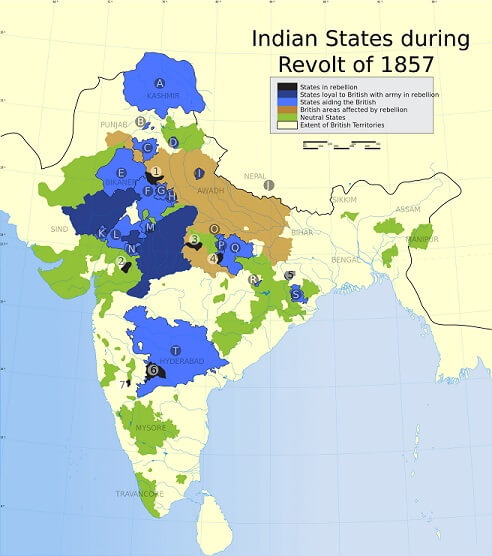

Verdicts on the Events of 1857

Verdicts on the Events of 1857