It is generally foolhardy to write about religion. An intricate web weaved around mythology shrouds every human religion. This makes it harder to separate fact from fiction. In a world where society’s fortunes waxed and waned with allegiance to different religions and the scientific investigation was not the common norm, pandemics re-shaped the world order from time to time.

In his popular novella, Of Mice and Men, John Steinbeck wistfully wrote that the best-laid schemes of mice and men often go awry. Such is also the story for most people when a pandemic arrives discreetly and swiftly. In 542, about thirty years before Prophet Muhammad was born, the Arabian Peninsula was in great turmoil. Three things were everywhere to be found: death, death, death. Even as far as Constantinople (modern Istanbul), more than ten thousand people were succumbing to death every day. Bubonic plague had arrived. Everywhere it went, the plague wrought havoc on the masses. There are many tales of cities where doors of all houses were hung open, where nobody was left to guard even the precious commodities like gold and jewels, where not a soul was left to talk to. Farmers died. Crops died. Markets died. Whoever was lucky enough to survive the plague perhaps wished for death than a life of such misery. The economic depression created by this sudden sweep of disaster manifested itself in the decades to come.

In such a crumbling society, the public lost any semblance of respect and loyalty toward their rulers. Even the ruler of the Holy Roman Empire (which as a matter of fact was neither Holy nor Roman nor an Empire anymore), Justinian, felt that he was standing on shaky ground. The pandemic tossed many smaller rulers and bred a fertile ground for a new faith to establish itself. In such an unstable world, Islam was born. The rise of Islam after the first century of its inception is legendary. The major reason for its sudden growth is that it originated in the right place at the right time. People had concluded that the polytheistic religions in that part of the world had failed in saving them. As society’s order was crumbling down, Islam provided an alternative vision of bliss to its believers while bringing stability amidst the chaos. Allegiances changed. Islam’s time had arrived and the world would not be the same again.

Eight hundred years later, the fortunes of millions in Europe and the fate of another religion was about to be transformed by a pandemic. In 1347, sailors coming back to the Sicilian coast in Italy unsuspectingly brought with them an uninvited guest. Black Death as the pandemic came to be called had arrived. It shall be the most fatal pandemic in human history. Europe had erected many congested and shabby cities in previous centuries. Unbeknownst to people, rats carried fleas that transmitted germs to humans in these cities with ease. In a society where taking a regular shower was abhorred, 30-60% of Europe’s population perished in less than five years. It then took Europe’s population two hundred years to reach the same level. However, the Black Death did not recede from generational memory for a long time to come. Many random outbreaks occurred almost every generation until 1700 when the Age of Enlightenment finally arrived.

In this tumultuous society, faith in Christianity was fast receding. The Almighty God and Pope had both failed. Church had failed. Death and destruction were evident everywhere. Again, a fertile ground for a new ideology. Thus, in 1517, a German professor of theology in the obscure town of Wittenberg in Germany posted Ninety-five Theses on the door of All Saints’ Church. This marked the beginning of the Protestant Reformation. Martin Luther’s petition against the clergy and re-interpretation of Jesus Christ’s message ushered an era of reasoning and common sense. Surely, if the position of the omnipotent Pope could be challenged, the existence of everything in the Universe could be questioned. Society started to rapidly come out of the Dark Ages. With the recent discovery of the Americas which had happened in 1492, Europe commenced on the path of Imperialism hand-in-hand with Science and Liberty. Europe’s time had arrived and the world would not be the same again.

Even today, religions are playing a big role in the spread of the pandemic. Whether be the Patient Zero in South Korea who transmitted the coronavirus in a church congregation, a Sikh priest who tested positive in Anandpur Sahib and transmitted the coronavirus to many, or the Tablighi Jamatis who now account for a large proportion of coronavirus cases in India, pandemics and religions do still go hand-in-hand. The last-mentioned ones have not only polarized public opinion in India but also brought disrepute to that wonderful and soul-fulfilling place in Dilwalon ki Dilli—Nizamuddin—the resting place of three great masters of poetry, music, and scholarship that the Indian-subcontinent has produced—Nizamuddin Auliya, Amir Khusrau, and Mirza Ghalib.

However, two chief factors shall distinguish the interplay between religion and pandemic from those past times discussed above and ours. First, we know infinitely more about every aspect related to the pandemic and its prevention than did people in those times: causes, diagnosis, transmission, vaccination, tracking, drug-delivery, mitigation, etc. This means that since from the past two centuries, most people are already wedded to the idea of accepting both God and Science simultaneously, faith in religion is less likely to witness a steep plunge. Second, the institution of religion as the opium of the masses has been replaced by nationalism. Religion still plays a major role in the politics of most nations but does not command an all-powerful influence as it did for most of human history. Thus, the change in world order now is more likely to be closely associated with the decline and emergence of nations rather than religions. It is altogether possible that this might occur along the lines of the single-most-important institution which distinguishes nations into two groups today: Democracy.

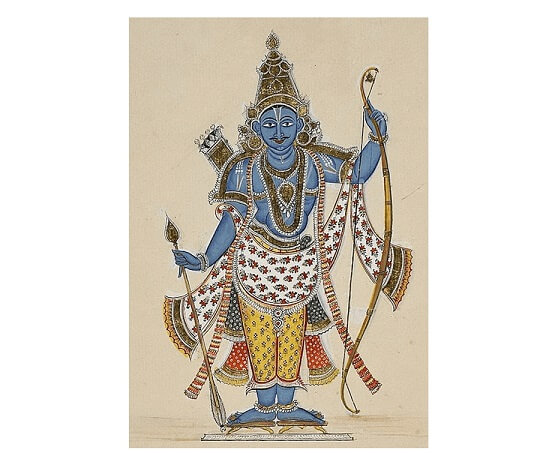

Rama, the Brilliant Politician

Rama, the Brilliant Politician